PINEHURST, N.C. – The lifesaving business is one Dr. Peter Ellman knows well.

PINEHURST, N.C. – The lifesaving business is one Dr. Peter Ellman knows well.

For 15 years now, Ellman, a cardiovascular and thoracic surgeon at FirstHealth’s Reid Heart Center, has changed the lives of thousands of patients and their families.

He has seen everything you can see in an operating room. He’s even saved the lives of other FirstHealth employees. On that occasion, when Ellman removed a benign tumor from a coworker’s chest, he had no way of knowing how impactful that procedure would be – both for the patient, Caryn Peterson, and himself.

The surgery, and its impact on Peterson’s life, would become a key cog in Ellman’s own health care journey, one that started early in life and wound its way to the organ transplant unit at UNC Hospital.

Family Tragedy Leads to Diagnosis

Ellman’s path to receiving an organ transplant began with a family tragedy he experienced as a teen.

At 19, Ellman’s mother died after suffering an unexpected brain aneurysm. Ellman said he received the news about his mother’s emergency just as he and his teammates on the Dartmouth University ski team were preparing to travel to the NCAA Skiing Championships.

“I was diverted from the airport to say goodbye to my mother while she was on life support. At the same time, my father told me her aneurysm was related to Polycystic Kidney Disease, which they found she had right then and there,” he said. “So, in addition to losing my mother, I was told I had a 50% chance of having this fatal disease.”

Dr. Ellman continued with his undergrad education and then went on to medical school, not thinking much about PKD until almost a decade later.

“I was a general surgery resident in my late 20s and while waiting for a trauma patient to get a CT scan in the middle of the night, ever the optimist, I was thinking maybe I didn’t have it,” he said. “I took an ultrasound probe and checked and saw that my kidneys were full of cysts. This was when I knew I had the disease. It was a little like knowing you have a ticking time bomb in you.”

After completing his education, residency and training, Ellman came to FirstHealth of the Carolinas in 2009. His kidney function was good, and he was ready to begin his career as a CVT surgeon.

“When I started working here my kidney function was normal, but I did get yearly labs. Around 2012 was when the function started to deteriorate, and every year I would hope that perhaps it would not progress, but every year those dreaded labs showed that indeed my function was deteriorating,” he said. “By 2021 my function had deteriorated to the point where I was on the brink of dialysis. That would have meant I was done with my career as a heart surgeon. My hope was that I would potentially be able to get transplanted before that happened.”

Life-Altering Encounter

Although Ellman’s kidney function continued to decline throughout the 2010s, his impact on patients and families only grew. Around Christmas in 2016, he had his first fateful meeting with Caryn Peterson, who was working as a regional director for FirstHealth clinic in multiple counties.

“Everything was going along fine. I was working, living a perfectly normal life, but I started getting cold-like symptoms and chest pressure, and I started losing my voice,” Peterson recalled. “It’s getting close to the holidays, and I knew I needed to get checked out. One test led to another, and I ended up seeing a radiologist who was very concerned. He arranged for me to see Dr. Ellman, who pulled me in and showed me a CT scan. He wasn’t 100% sure but told me that I could have a tumor in my chest. It was shocking news.”

Soon after, Ellman and Peterson were discussing surgical options for removing the tumor.

“She was symptomatic from a large tumor about the size of a cantaloupe in the center of her chest. This was compressing her heart and lungs to extent that it was causing her symptoms. We were able to operate the next day and take it out completely. It turned out to be benign, thankfully. She made a quick and complete recovery,” Ellman said.

Peterson said she was “blown away” by the care she received.

“Obviously, he’s a remarkable surgeon. Beforehand he went into a lot of detail and helped explain the best and worst-case scenarios, so I knew how to prepare mentally. And then he went in and removed it, which is incredible that these surgeons can do these sorts of things day in and day out,” she said. “And on the other end of it, as I’m recovering and regaining my strength, I’m just so grateful for that sort of ability.”

After Peterson’s recovery, a career change led her to the CVT and cardiology clinics, where she became their new director. What seemed like a natural evolution in her career would turn out to be much bigger for Peterson and, more importantly, for the surgeon who had saved her life.

Peterson's Gift

By the end of 2021, as he continued performing surgeries and caring for patients and their families, Ellman’s kidney function had deteriorated to the point that he was referred to the UNC transplantation center.

By the end of 2021, as he continued performing surgeries and caring for patients and their families, Ellman’s kidney function had deteriorated to the point that he was referred to the UNC transplantation center.

Kidney transplantation can happen with either a living or a deceased donor. Because people can live with only one kidney, it allows a living donor to give life and live the rest of their life with one kidney. Donation is an incredible gift to the recipient, allowing them to avoid going on dialysis and ensuring they can return to a completely normal life, doing what they have always done. Those without a living donor often will go on a deceased donor waiting list, a process that on average means a seven-year wait. During the time, someone with failing kidneys would like get dialysis three times a week, and they certainly would not be able to do something physically demanding, like heart surgery in Ellman’s case.

“When I went to orientation for transplantation at UNC and learned about the options, I was hopeful that I would be a candidate for a living donor. Thankfully my wife Sarah had always told me that she would give me one of her kidneys if I needed it, and she started the work up to be my donor,” Ellman said. “My wife is the toughest person I know. She started the testing to see if she was a match. My kidney specialist here in Pinehurst asked me if I also wanted to go to orientation about dialysis as a back-up plan. I told him, ‘No thanks! No plan B!’ He laughed and said, ‘OK, OK!’”

Around this time, as his condition worsened, Ellman began telling those close to him at work about his circumstance.

“I met with Caryn, who was running our clinic, to tell her that in early 2022 I would be out for about two months because I was in kidney failure from Polycystic Kidney Disease. I was just letting her know from a planning standpoint. Certainly, she was surprised because this was not something I had shared with anyone over the years—there was no reason to professionally,” he said.

Dr. Ellman returned to his office and got back to work, and his phone rang five minutes later.

“Caryn called and said she wanted to come down to my office to chat,” he recalled.

It was at that point, only learning five minutes before that he would need a transplant, that Caryn said that she wanted to be Ellman’s donor. Ellman was initially very reluctant about Peterson’s offer, in addition to being amazed with the speed with which Caryn made that decision.

“It is hard to describe what it feels like for someone to come to you and say that they would risk their life for you without hesitation,” he said.

After talking to his wife, Ellman thought it was best to just stick with the original plan of Sarah as the donor.

“I said, ‘OK, I get all that, but I’m going to get tested,’” Peterson said. “I remember going outside and walking around Reid Heart Center’s parking lot, and I felt good. It’s weird to explain it.”

Peterson’s offer to donate led to testing to see if her kidney was a match. And it also led to a heart-to-heart conversation with Sarah Ellman at a Christmas party.

“Sarah came up to me, and I remember she held my hand and said that it was beyond amazing that I offered. And she said, ‘We could never let you do that.’” Peterson recalled. “And I remember looking at her and saying, ‘Sarah, if you both have this surgery, who is going to take care of him? Who is going to take care of you? What about your children?’ And we had this amazing conversation.”

Peterson said the momentum to donate kept “stirring in her,” and she went down the path, starting with a full round of medical tests, including an extensive review of her entire medical history, including the history of the chest tumor Ellman had removed.

“I contacted UNC and did the initial screening. This sounds crazy, but I knew before they confirmed that I was a match,” she said. “I remember the day UNC called to tell me, and I went over to see Peter. He said, ‘Oh, my gosh.’ And I said we’re going to do this.”

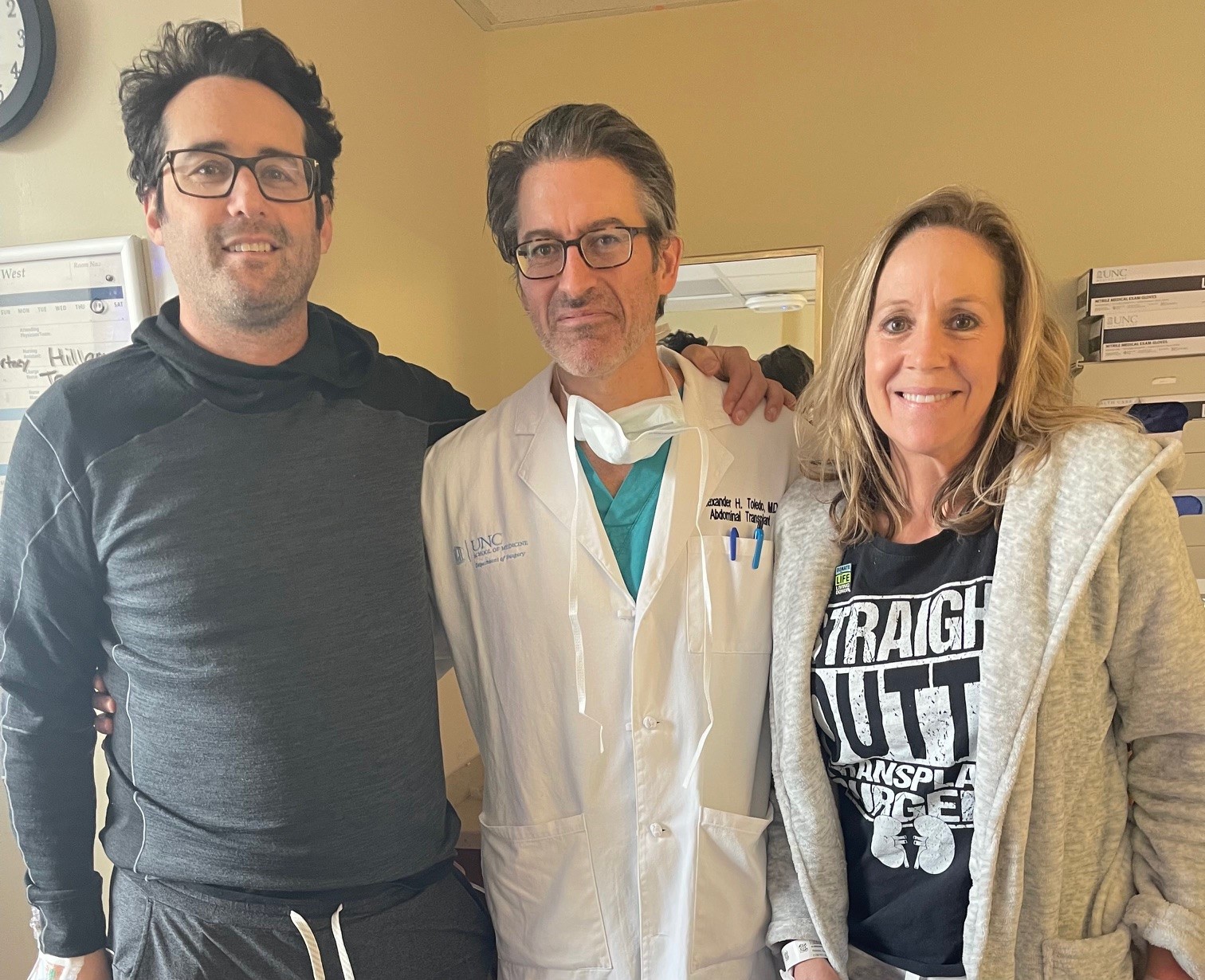

After clearing a few final testing hurdles, there was one choice left for Ellman and Peterson – picking a date for the transplant surgeries. There was only one choice for Ellman. “We actually did the transplant surgeries in March of 2022, on my mother’s birthday,” Ellman said. “It was a Wednesday, and amazingly enough I had been able to perform a heart surgery on Monday of the same week.”

Two months after the surgery, Ellman was back at work. It would take much longer to start to feel “normal” again, but in 2024 he is exercising again and able to fulfill his passion of taking care of others.

“Right after the surgery you are on a ton of medication, so you feel jittery and not yourself and you are also recovering from the surgery itself,” he said. “I started to feel good after about a year, and now I’ve started running again. Life has gone back to full color. I think one of the hardest things for a human being to deal with is uncertainty. We can deal with bad stuff when we know what it is and what we’ve got to deal with. Now, I no longer have the uncertainty hanging over me. The rain clouds have lifted, so to speak.”

Reflecting on the last 8-plus years, Peterson leans into her faith when explaining what her journey from patient to donor looked and felt like.

“There are moments in life when people have peace about the decisions they make. Maybe you don’t know the why now and maybe you never really know the why, but you have peace,” she said. “The second part is the impact Dr. Ellman’s had on people and the impact he will continue to have. If heart surgery is what he loves to do and how he can help people, why would we not let him continue to do that? I believe in my core that we are here to serve others, and everybody has different ways of doing it. In that sense, this decision to donate was made for me, and that’s amazing.”